Finding our way (avoiding the avalanche of management prescription)

Time to reset?

Apparently it’s time to reset a lot of things. Until a few months ago all that most of us were ever asked to reset were a lot of passwords and the occasional machine (‘try turning it off and back on again’). Now, just in the world of organisational development, countless reports tell us we need to reset everything from strategy, goals, operating model and workforce to workplace, culture, leadership and decision-making.

There’s no denying the disruption brought by the pandemic or the volume of change it demands in response but I question whether resetting (‘to set again in a different way or position’, OED) is really what’s needed.

The language is interesting. Over a hundred years since the death of Frederick Taylor we haven’t managed to throw off the reassuringly manageable notion of the organisation as machine. Perhaps it’s something we cling to tighter than ever now (in the same way as we reach out for the ‘new normal’) as a response to uncertainty and defence against anxiety.

Inevitably, most organisations are still discovering and making sense of the implications of Covid-19, and at this stage there are more questions than answers. Google searches for ‘cultural reset’ are up 1,600% on a year ago, most of them just asking what it means. The sense of doubt and uncertainty is palpable.

Last month’s Management Today future of work conference, ‘Leading in the Hybrid Workplace’ was a good illustration. The journal’s editor Adam Gale opened with a list of questions his readers are grappling with:

- can you manage teams as effectively?

- can you shape culture and a sense of purpose and vision as effectively?

- can you avoid resentment and division building between those who choose to come in to the office and those who don’t?

- are the benefits to productivity and the cost base worth the headache?

A diverse field of leaders and HR people shared their experiences of responding to the sudden fact of a hybrid workforce but revealed that we’re barely out of the blocks when it comes to creating a hybrid workplace and that the answer to all these questions is ‘we don’t know yet’.

An avalanche of prescription

Consequently we may be more vulnerable than usual to the prescriptions that make the Management Practices Market go round. And you can’t have failed to notice there’s a lot of them about, all of them broadcast and many accepted as if (a) we knew the answer and (b) the answer could be the same in different times and places.

They take familiar forms, including:

- Leading by numbers (Three strategies for leading effectively amid Covid-19, Five ways for business leaders to reassure their people and reduce uncertainty, Three ways to create a necessary culture shift amid Covid-19….)

- The promise of quick solutions to intractable problems (How to accelerate digital, Pathways to faster innovation, Stepping stones to an agile enterprise….)

- And additions to the already unworkably long list of ‘leaderships’ for us to practice and types of leader for us to be (Responsible Leadership, Resilient Leadership and The Kinetic Leader, whatever that is….)

The lifecycle of prescriptions is the subject of research that is well-established but – for obvious reasons – little-publicised. Leaders and organisation developers looking to understand what influences them and their organisations would do well to study it. In their recent review of the literature Fads and Fashions in Management Practices: Taking Stock and Looking Forward [1], Piazza and Abrahamson note that, although researchers use different words to describe what it is that goes in and out of fashion (ideas, concepts, panaceas, techniques, practices), they tend to agree what they’re looking at are prescriptions for managing organisations.

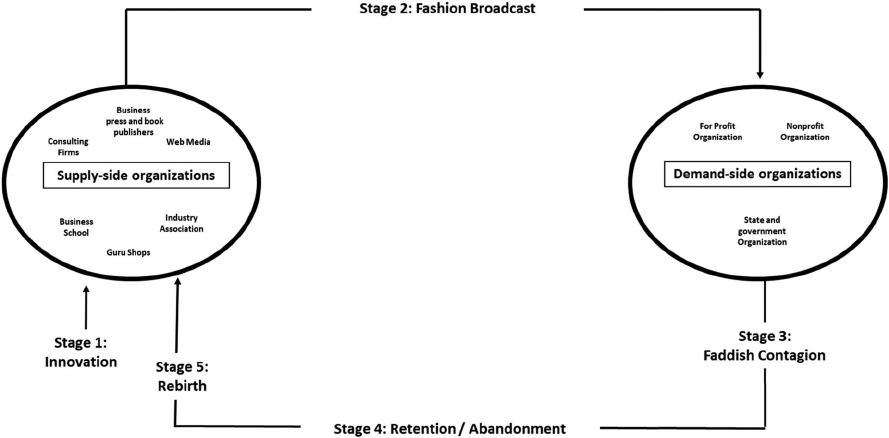

That they summarise what’s known about the market in terms of ‘innovation > fashionable broadcast > faddish contagion > selective retention > abandonment > rebirth’ says a lot about the caution required (see figure below). They conclude that demand is driven by a combination of the ineffectiveness of solutions and our appetite for novelty, noting also that suppliers need management practices to become unfashionable to make room for new ones.

Their ‘looking forward’ focuses on the growing number of suppliers of prescriptions and on the wider broadcast of prescriptions and their deeper penetration into organisations made possible by the internet in general and by LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and TED in particular.

Their ‘looking forward’ focuses on the growing number of suppliers of prescriptions and on the wider broadcast of prescriptions and their deeper penetration into organisations made possible by the internet in general and by LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and TED in particular.

Clearly, the deluge is not about to abate.

If not prescribed practices, then what?

Gary Hamel suggests that deep, sustained change depends on paying less attention to practices and more to principles. He observes that management writing tends to focus on the tactical and that case studies about W.L. Gore, Spotify, Haier and other post-bureaucratic pioneers have had little effect [2].

“When corporate leaders look at those outliers, they ask, what they should do differently? This is the wrong question. The question should be, how do they think differently? What are the principles you have to start with to end up with an organization that breaks the bureaucratic mold in every way? … When leaders read these management books and articles, they try to graft the new practices onto the old philosophical rootstock and the graft doesn’t take.”

It makes me wonder how many people have read the Netflix culture deck, so frequently downloaded and shared since first made public in 2009. Intended to be actionable, it expressed the company’s culture primarily in terms of behaviours and practices (for example, ‘Managers: when you are tempted to “control” your people, ask yourself what context you could set instead’). And, by contrast, how many have read Patty McCord, the chief architect of that culture, describe not only the principles of their approach but how they arrived at these and how they developed their culture over time (either in her book Powerful or HBR article How Netflix Reinvented HR)? For every company that’s sought to understand that process and use it to help them do the work of developing their own culture, I guess there might be a thousand who have sought to emulate the Netflix culture at the level of its practices or trappings.

But maybe the way forward is to wean ourselves off both ‘best practices’ and exemplary companies or leaders… and find our own way. In a review of 1,700 academic, professional, business, and trade publications from a 17-year period [3] Miller and Hartwick observed the rise and fall of many business fads and identified their qualities (which included prescription, of course). Among the fads they looked at successes that had changed many companies profoundly (e.g. TQM), and found that these ‘classics’ typically emerged, not from the writings of academics or consultants but ‘out of practitioner responses to economic, social, and competitive challenges’.

Today, for many, the challenges are great. With that comes widespread recognition of the need for change and new ways of working. With that comes opportunity for realignment on all sorts of levels. If, that is, we’re prepared to do the work. We could take our pick of the prescribed practices but the inconvenient truth is that what worked there and then is unlikely to work here and now. So what’s called for is a process of discovering and responding to what’s needed here and now. Equally, what works here now is unlikely to work here in the future. So what’s called for is not a process of discovery to inform a reset but a process of continual experiment and adaptation, without which we will always be moving towards yesterday’s ends by yesterday’s means.

[1] Piazza A, Abrahamson E. Fads and Fashions in Management Practices: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 22, 264–286 (2020)

[2] Hamel G. (2020) Leadership Lessons From The Coronavirus Crisis. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2020/04/23/gary-hamel-hard-lessons-from-the-coronavirus-crisis/?sh=2c47a0223c1e (Accessed: November 16, 2020)

[3] Miller D, Hartwick J. Spotting management fads. Harvard Business Review, 80(10):26. (2002)